90

Watch It Chrissy

Story by David Chase

Teleplay by Terence Winter and Robin Green & Mitchell Burgess

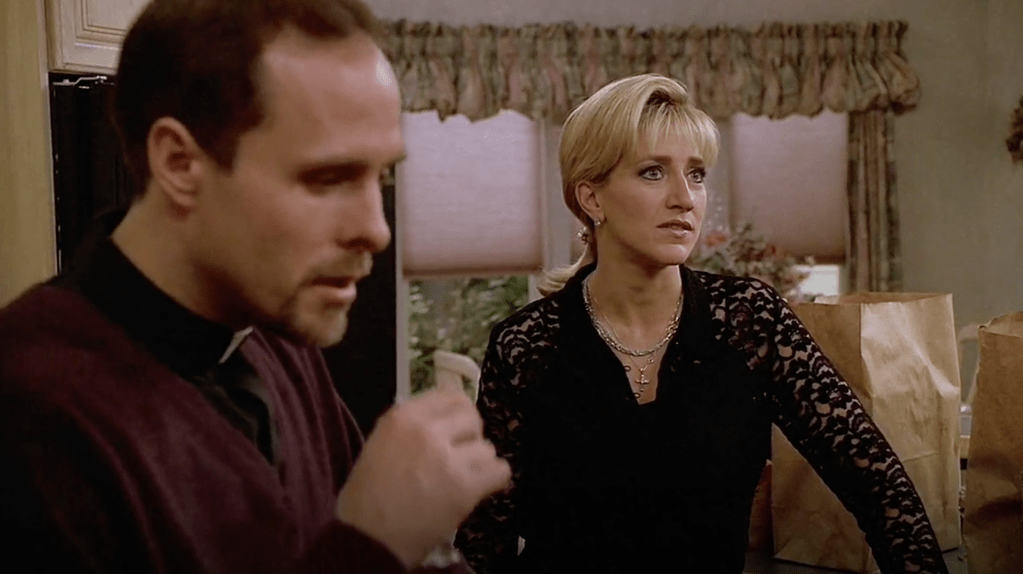

Christopher’s intervention.

_______________________________

I understand that, outside the cut to black, this is the most iconic scene in the series. Putting it at #90 is not a knock; anything in the Top 100 is sacred among Sopranos. After all, Christopher’s intervention is just highlight after highlight:

- Dominic, the “scumbag” and an intervention veteran, clearly takes recovery seriously. For the rest of the occupants in Christopher’s living room, interventions are unfamiliar, to say the least. Watching them navigate this totally foreign concept is hilarious.

- When Adriana states that Christopher “can no longer function as a man” because of heroin, Paulie’s facial reaction is pure gold.

- Tony puts his sociopathic affection for animals on full display as he reams out Christopher for accidentally killing Cosette. He can’t stop dwelling on it, so Chase includes the series’ most direct and significant foreshadow: “You killed little Cosette. I oughta suffocate you, you little prick!”

- To understand why Christopher may have killed the dog, Paulie earnestly asks, “What was it barking?” It’s hilarious.

- Every single character in this show is allergic to accountability. When Sil says his piece, Christopher points out Sil’s infidelity. When Paulie lets Christopher “take his medicine,” Christopher distracts Paulie’s accusations by exposing Paulie’s “Pine Barrens” faux paus to Tony.

- Tony reacts with disgust when Carmela comments how Christopher was high at Livia’s repast, showing just how on edge and distracted Tony was by Janice, Artie, and the precarious tension in the room to give a shit about Christopher’s appearance.

- When the guys start beating the shit out of Christopher for saying “Great my own mother. Fuck you, you fuckin hewah,” Christopher goes after Benny because 1) he’s far from untouchable and 2) He can’t allow someone beneath him to get the better of him

- Adriana and Carmela hear and witness things they know to be true, but routinely tune out: beating up Christopher when he crosses the line, and divulging Sil’s infidelity.

Christopher’s addiction is central to the arc that makes him one of the best fictional characters of all time. But, I’ll save those analyses for other scene write-ups, and limit this one to the intervention’s highlight reel.

89

For God’s sake! We bend more rules than the Catholic Church!

Written by Terence Winter

Directed by Jack Bender

Two bosses, an underboss, a consigliere, and an acting boss sit down to discuss Ralph’s “off color remark.”

_______________________________

In light of Ralph’s joke, New Jersey, New York, and the Esplanade are forced into a stalemate. Junior phones into a sit down between Carmine, John, Tony, and Sil to offer his senior insight. Just like Carmine earlier in the episode, Ralph’s joke confuses Junior. This, complemented with Carmine and Junior’s unfamiliarity with cell phones, makes for quite the comedic spectacle. As the sit down progresses, John’s leverage weakens when he refuses to admit who relayed the joke to him. By not voicing this agreement, Junior demonstrates loyalty to Tony. He waits until he and Tony are in private and remarks “real lack of standards, your generation,” and reminds Tony that John was right to say “if this were years ago would I even have had to ask?” Carmine’s insistence on prioritizing money over Ginny’s “honor,” coupled with John and Junior’s point on how this issue would’ve played out back in the day, speaks volumes to the evolution of La Cosa Nostra’s rulebook, and perhaps society’s as a whole. This, of course, is tied together by John’s “I mean what happened to this thing?! For God’s sake, we bend more rules than the Catholic Church!” Junior smirks in agreement.

Additional Notes:

- Following his house arrest, this is one of only two occasions where Junior talks business with anyone besides Richie, Bobby, or Tony, so it’s quite the treat.

- Sil casually compares themselves to international terrorists as he explains to Carmine they dispose of phones after one call, just like the Taliban.

- Carmine hurries the meeting along with “Let’s get started. My daughter-in-law’s coming here with the baby later.” This is textbook regularness of life dialogue that makes The Sopranos the greatest show of all time. It has nothing to do with the plot, and everything to do with depicting a believable fictional universe that makes you forget you’re watching fiction.

- We learn a lot about the mob’s rulebook throughout the series. When Tony objects to John’s refusal to rat on the gossiper, the audience learns that Paulie’s disloyal mouth is a bigger no-no than the joke itself.

- John’s “I want to avenge her honor as is my right to do!” is funny as hell, and very telling. Among soldiers, John’s determination to whack Ralph demonstrates genuine love for his wife. Most other guys would be enraged by a similar joke, but they’d be defending their ego more than their wife’s honor.

88

But I think you need to look at yourself

Written by David Chase

Directed by John Patterson

Carmela’s jealousy of Rosalie drives her to accuse Father Phil of exactly what she too is guilty of.

_______________________________

Carmela brings by pasta to the church to mang’ with Father Phil, only to walk in on Rosalie stealing her thunder. Ever so jealous and hurt by the sight of Rosalie sharing her own pasta with Father Phil, Carmela empties her dish in the garbage like a 13 year old girl. Later, Carmela returns home to Father Phil oddly alone in her own kitchen (the maid let him in), and she immediately turns on her passive aggressive switch. Father Phil makes small talk by mentioning the storm that’s all over the news which, I think, is crucial; if David Chase is as brilliant and deliberate as I think he is, then the episode briefly mentions this impending storm to callback to the last time there was a storm in The Sopranos. During a loud thunderstorm that echoes throughout the Soprano house in “College,” Father Phil and Carmela had a sleepover (and confession!) where they came very, very close to doing a little more than an innocent game of “Name that Pope.” As Carmela grows feistier, Father Phil sets her off with “…as I was saying, my real concern for Tony,” to which Carmela snaps back “Father, he doesn’t give a flying fuck. You know it, and I know it…He’s a sinner, Father. And you come up here and you eat his steaks, and you use his home entertainment center…But I think you need to look at yourself. Call this an intervention. Because I think you have this MO where you manipulate spiritually thirsty women, and I think a lot of it is tied up with food, somehow, as well as the sexual tension game.”

Floored and convicted, Father Phil leaves. In a textbook demonstration of narcissism, Carmela accuses Father Phil of exactly what she too is guilty of. Though her predicament is quite different, she too enjoys the “whiff of sexuality.” She craves the attention Father Phil readily gives, and that Tony does not. Raising the stakes, Carmela highlights how, while Father Phil allegedly wants to help Tony become a better person, he doesn’t hesitate to eat his food, drink his wine, or watch his television set. This directly correlates to Carmela’s own complicity, as underlined by her therapy session with Dr. Krakower in Season 3’s “Second Opinion.” Carmela is in luck, so long as someone else commits the same sins as her, as identifying and criticizing someone else’s culpability is an effective tactic for blocking out her own faults. Carmela’s entirely correct in her assessment of Father Phil, and it would be quite brave and heartwarming if it were intended as friendly, helpful advice. But, she’s a hypocrite, and her spite and jealousy of Father Phil “cheating” on Carmela with her best friend Rosalie (a freshly widowed woman!) exclusively inspire her harangue. Even with Jackie Aprile in the ground, Carmela and her narcissism have nothing better to do than to interrupt Rosalie and her flirtatious pasta feasts with Father Phil.

87

This is such bullshit!

Written by Lawrence Konner

Directed by John Patterson

At Jackie Jr.’s funeral repast, Uncle Junior sings for an audience, Paulie cries to “Uncle John,” and Meadow drinks away the trauma of being a mob boss’ daughter.

_______________________________

When Paulie approaches Tony at Jackie Jr’s funeral repast, he, like Ralph in “He Is Risen,” denies the boss’ drink offer, an offense that had Paulie calling for Ralph’s head (“Let’s whack this cocksucker and be done with it”). As the disgruntled Paulie departs, Tony’s facial expression demonstrates his wariness toward Paulie’s inbound insubordination in light of his ruling in that “Morristown bullshit,” which threw a wrench in Paulie’s plans to fund his mother’s move to Green Grove. Immediately after, Johnny Sack catches the slighted and vulnerable NJ underling in the parking lot, and subtly instigates the clueless Paulie to air dirty laundry. Paulie feels he’s been disrespected and “that maybe Tony fundamentally don’t respect the elderly,” (Paulie’s reactive judgment on how he and Tony have treated their mothers). Swiftly, Paulie gains a confidant and John secures a rat. This quick parking lot cigarette break serves as the second domino to fall in the NJ-NY feud that lasts all the way through the finale, as Paulie’s loose lips lead to the irreparable esplanade dispute in Season 4.

Back inside, Tony sits beside his uncle, who points out that Jackie Jr. “was always a dumb fuck,” and how the turnout wouldn’t have been so crappy if Jackie Sr. were still around; an ominous reminder of just how circumstantial loyalty can be in this thing. And, speaking of insubordination, Tony observes Ralph (who’s already jeopardized his newfound good standing with Tony by enabling Jackie Jr.) canoodling with Janice, and Meadow on a drunken mission. Meadow, who’s been juggling her loyalty and denial all episode, reciprocates this mockery of Jackie’s remembrance by tossing bread at her great uncle as he sings to an immersed audience. As Tony chases Meadow outside, he looks legitimately frightened when she screams in his face “This is such bullshit!” Clearly, Tony fears the prospect of Meadow exposing the truth of Jackie Jr.’s death.

86

I got the world by the balls and I can’t stop feelin’ like I’m a fuckin’ loser

Written by Frank Renzulli

Directed by John Patterson

Tony envies happy-go-lucky people.

_______________________________

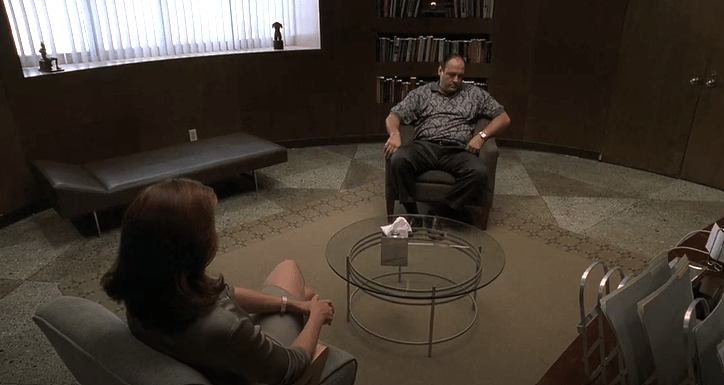

In the prior episode, Big Girls Don’t Cry, Tony visits Hesh and vents about his untethered, unjustified anger (evidently, Tony’s in touch with his feelings, unlike Gary Cooper!) In his second Melfi visit since his therapy hiatus, Tony unloads:

Tony: “I don’t know who the fuck I’m angry at. I’m just angry, okay? Why the fuck am I here? I even asked to come back. I got the world by the balls and I can’t stop feeling like I’m a fuckin’ loser.”

Melfi: “Who makes you feel like a loser, your mother?”

Tony: “Oh, please, we wasted enough oxygen on that one. It’s everything and everybody. I see some guy walking down the street, you know, with a clear head. You know the type. He’s always fuckin’ whistling like the happy fuckin’ wanderer. I just want to go up to him and I just want to rip his throat open. I want to fuckin’ grab him and pummel him right there for no reason. Why should I give a shit if a guy’s got a clear head? I should say ‘a salut’, good for you…Remember the first time I came here? I said the kind of man I admire is Gary Cooper, the strong, silent type. And how all Americans, all they’re doin’ is cryin’ and confessin’ and complainin’. A bunch of fuckin’ pussies. Fuck ‘em!”

The series’ pilot establishes the stress and depression that wears Tony down. Tony confronts these feelings in an uncharacteristic, but telling, approach. Instead of merely announcing that he’s depressed and stressed, he actually acknowledges why he is; he doesn’t have a clear head. His envy toward stress-free people, and the impulse to pummel them, thoroughly demonstrates Tony’s loathing toward his own life choices. And, Tony’s “I got the world by the balls and I can’t stop feeling like I’m a fuckin’ loser” not only mirrors his rant to Hesh, but defines depression to a T (pun intended).

Tony then accuses Melfi of making him feel like a victim, something that contradicts the essence of Gary Cooper and leaves Tony resenting himself. And, Tony’s right: Melfi replies “Your parents made it impossible for you to experience joy,” much to Tony’s displeasure. Melfi, of course, is right about Livia and Johnny Boy’s trauma-inducing parenting. But, much like Carmela, she shifts the blame away from Tony and excuses his own personal choices. That being said, he brushes off Melfi’s spot on hypothesis (“Who makes you feel like a loser, your mother?”), as he routinely dances around his mother’s resentment of him.

85

How are we gonna save this kid?

Written by Lawrence Konner

Directed by John Patterson

Tony unravels after military school plans go awry.

_______________________________

After learning of AJ’s panic attacks, Tony breaks down in Melfi’s office: “Obviously, we can’t send him to military school. Pediatrician said. He’s got that putrid, rotten, fuckin’ Soprano gene.” Melfi cuts Tony deep when she somberly replies “When you blame your genes, you’re really blaming yourself. And that’s what we should be talking about.” Tony distracts from the point at hand with bullshit about suing Verbum Dei for negligence, and the camera cuts back to Melfi; she tilts her head and drops her eyes, defeated that Tony ignores her useful insight that could’ve actually gotten him somewhere. As usual, Tony refuses to confront the consequences of his half-assed parenting. When Tony pauses and chokes up, Melfi re-directs the focus, leaving Tony to insist “You don’t understand…We can’t send him to that place…How are we gonna save this kid?” Boom, the camera cuts to Jackie Jr.’s casket as it’s removed from the hearse. “How are we gonna save this kid” is such beautiful writing, complemented by an emotional and chilling delivery from Gandolfini. The seemingly unsolvable question also dichotomizes Tony’s parenting; his desperate and scared tone certainly conveys genuine love for his son, but his dependence on military school illustrates his neglect for fatherly duties. Tony met Gloria Trillo in 3.08 and AJ nearly got expelled in 3.09 for vandalizing the Verbum Dei pool. From that point until his expulsion in 3.13, Tony spent more time and energy on his new goomah than his son who teetered on the brink of expulsion. Tony is capable, but unwilling, to be there for AJ.

84

Thank you Silvio, for your unwavering loyalty

Written and Directed by David Chase

Tony visits Sil, and tenderly expresses his gratitude.

_______________________________

The Sopranos’ farewell to Sil pays homage to loyalty. The consigliere’s steadfast loyalty extended far beyond omertá; all he did was make Tony’s life easier. He was the only guy who caused no problems for Tony (despite forgivable defiance in “No Show” and “Christopher”). Chase times this farewell quite deliberately; in the scene prior, Tony’s lawyer, Neil Mink, relays that an informant will give grand jury testimony, and predicts there’s an 80-90% chance Tony will be indicted. Cooperating is an obvious no-no in this “certain Italian-American subculture,” and The Sopranos extensively illustrates Tony’s trauma from rats and unshakeable fear of incarceration. As America (and its mobsters) continued to separate itself from the principles of Gary Cooper (The Strong, Silent Type), rats became the norm: Jimmy Altieri, Pussy Bonpensiero, Ray Curto, Gene Pontecorvo, Carlo Gervasi, Adriana La Cerva, and very possibly Christopher Moltisanti had Tony not beaten him to the punch. In light of Mink’s grim news, Tony takes his time silently staring at a lifeless Sil, and clenches his confidant’s hand as he prepares to meet his own fate. The embrace effectively conveys what Tony’s thinking: “In this slippery thing of ours, thank you for being the only guy I could trust wholeheartedly.”

Additional Notes

- Chase makes a curious decision to play Little Miss Sunshine on the hospital room’s television. I think Abigail Breslin’s adorably joyous reaction is there to contrast Tony’s demise that has finally arrived. Additionally, Abigail Breslin’s character serves as an amplified version of “the happy fuckin’ wanderer,” whom Tony ranted about in therapy five seasons earlier.

- While I do passionately hate Silvio Dante and Stevie Van Zandt’s attempt to act, I’m not shallow enough to celebrate his demise. That being said, it’s no coincidence that, in the only Sil-centric scene on this list, he does not speak.

- While Bobby was trustworthy, he didn’t become a confidant until the latter half of the final season. Patsy could never be fully trusted given his twin’s murder, which contributes to the sound theory that the family’s accountant had Tony whacked. Paulie couldn’t be trusted because of his enormous mouth, and Christopher was killed once Tony’s faith in him expired.

- Silvio’s loyalty extended beyond keeping his mouth shut. All he did was make Tony’s life easier. He was the only guy who didn’t cause any problems for Tony (despite a few forgivable slip ups in No Show and Christopher).

83

What are you doing home at this hour?

Written by Jason Cahill

Directed by Allen Coulter

Carmela steps in place for Melfi.

_______________________________

As Carmela grapples with her discovery that Tony’s therapist is a female, the couple has a poolside heart to heart in Season 1’s “Pax Soprana.” Carmela professes “I’ve been thinking a lot about this. I was jealous of her ability to help you. To be sort of a salvation to you. I talked to Father Phil and…I want to be that woman in your life.” Tony’s top insecurity, above all else, is his impossibly volatile relationship with his mother. While Tony lacks this ideal, standard form of a female caretaker (or “salvation”), Melfi, not Carmela, substitutes Livia. But, after Tony tries to win back Melfi’s care following the events of “I Dream of Jeannie Cusamano,” Melfi puts her foot down as she orders Tony to “get out of my life,” leaving Chase to employ an absolutely beautiful contrast to what just transpired with Melfi.

Tony returns home (at a time of day when he’s never home, Carmela notes) and approaches his wife like a desperate, lonely dog in need of tender love and care. Their actions speak for the scene’s silence, as Tony aimlessly follows Carmela into the kitchen and accepts her offer to heat up pasta. She serves him, rubs his back with the tender love and care he craves, and sits beside her husband upon his request. He gazes at Carmela with appreciation as she sorts through the mail; longing, but unwilling, to open up to her. This is such a careful, subtle, and effective demonstration of Carmela’s yearning for Tony to lean on her. Tony’s timidity throughout the scene reflects his unwillingness to grant Carmela the privilege of being open with her. Melfi and Livia have something on Tony that Carmela will never have: power. Tony must limit his vulnerability with Carmela because the more he shares with her, the more power he gives her by marking her an equal – and Tony’s preferred lifestyle depends on owning much, much more power in the marriage. It’s a truly beautiful scene to close out the Season 2 premiere.

82

You’ve caused much suffering yourself, haven’t you?

Story By David Chase

Teleplay by Terence Winter and Robin Green & Mitchell Burgess

Directed by Alan Taylor

Tony distracts dodges the insurmountable pain he inflicts on others.

_______________________________

Tony orders an emotional Furio to get over his father’s passing, which cuts to Tony sobbing to Melfi about Pie-O-My’s savage death (among other things). Tony calls back to his Season 1 self-diagnosis as “the sad clown” – a front he puts on for his family and associates by laughing on the outside and crying on the inside. As a therapy veteran, Tony has come to understand how stressful it is to bear this front’s burden. Tony grows hysterical over both a horse’s death and the departure of backyard pool ducks, leaving Melfi to observe “you haven’t grieved this way for people,” evidencing Yochelson’s The Criminal Personality, the study Melfi begrudgingly reads in “Blue Comet.” The study reads “the criminal’s sentimentality reveals itself in compassion for babies and pets.” Naturally, Tony grows defensive and chastises Melfi for psychoanalyzing his raw emotion in light of a tragedy.

Tony further validates the next part of the study (“The criminal uses insight to justify heinous acts”) by ranting about the world’s brutality despite a loving, all-powerful God. In addition to Pie-O-My’s death, he mentions Justin Cifaretto’s life altering injury (Melfi: “How awful for the parents.” Tony: “Yeah”), Christopher’s heroin problem, and 9/11. It becomes evident that Tony laments about the suffering of the innocent to distract from his own transgressions. It’s the same rationalization concept Tony applies in “From Where to Eternity,” when Tony tries to exonerate his own sins by underscoring how wealthy, corrupt American businessmen exploit Italian immigrants for labor. Unmistakably, Tony validates the next part of Yochelson’s study: “The criminal uses insight to justify heinous acts.” Boldly, Melfi takes the opportunity to bring Tony back down to Earth, and gently reminds him “You’ve caused much suffering yourself, haven’t you?” Melfi catches Tony off guard, and he reluctantly and shamefully nods his head.

Additional Notes:

- With Tony in a coma, Carmela visits Melfi in “Mayham.” She replicates Tony’s methods to “justify heinous acts” with “…because there are far bigger crooks than my husband.”

- Melfi’s “That being said, it is a horse” feels like a callback to John’s “She was a hewah, Tony” and Ralph’s “A) She was a hewah”

- Tony says “I know it’s fuckin’ ridiculous, but I feel like the Reverend Rodney King Jr. You know- ‘Why can’t we just all get along?’” In “Kennedy and Heidi,” AJ concludes his rant about the world’s brutality and cries to his therapist with “I mean everything is so fucked up. Why can’t we all just get along?”

81

For some reason, I’m scared

Written by Matthew Weiner

Directed by Jack Bender

Meadow rescues Tony from the precipice of hell.

_______________________________

The coma dream sequence explores Tony at an identity crossroads, and what that means for his place in the afterlife. The dream captures his longing for an identity like Kevin Finnerty’s: a good, ordinary man who does honest work and loves his family, rather than a soulless mob boss who preys upon the innocent, drives his mistress to suicide, and neglects his son. Season 2’s “From Where to Eternity” highlights the great mystery of the afterlife and the consequences of mortal sins; Paulie and Carmela go crazy over Christopher’s pitstop in hell, while Tony doesn’t bat an eye. Four seasons later and barely clinging to life, the fear of hell consumes Tony’s subconscious for two whole episodes as he navigates purgatory. As Paulie’s pessimistic blabbering jeopardizes the stability of Tony’s coma, Kevin Finnerty approaches a beautiful, moonlit house. An identity-less Tony Blundetto (I’ll refer to him as Buscemi) meets him front and center to greet him:

Finnerty: “Excuse me. Is this the Finnerty reunion?”

Buscemi: “Hello there. They’re waiting for you.”

Finnerty: “Me?”

Buscemi: “Of course.”

Finnerty: “Has Kevin Finnerty arrived?”

Buscemi: “We don’t talk like that here.”

Finnerty: “What do you mean?”

Buscemi: “Your family’s inside.”

Finnerty: “What family?”

Buscemi: “They’re here to welcome you.”

Finnerty: “I don’t understand.”

Buscemi: “You’re going home.”

Finnerty: “I am?”

- Kevin Finnerty turns toward the house and sees an older woman on the porch, her face shielded by a pillar. She quickly retreats back inside. This closely resembles Tony’s dream in “Calling All Cars,” where Tony peers into a house to find a woman descending a staircase. Both women are clearly Livia, but this time, she’s in hell. This haunting image highlights the show’s overarching theme of Tony’s ultimate fate- be it prison, death, or eternal damnation. On the brink of death, Tony grapples with this terrifying reality in his dream state.

Buscemi: “Everyone’s in there. You can’t bring business in there.”

- Unsurprisingly, nearly everyone in Tony’s life is doomed for hell. And, he can’t mix the joys of life on earth with his eternal punishment.

Little Girl: “Daddy!”

Finnerty: “I lost my real briefcase. My whole life was in it.”

Little Girl: “Don’t go, Daddy!”

Finnerty: “What is that?”

Buscemi: “Briefcases aren’t allowed.”

Finnerty: “No, the voice.”

Buscemi: “Please, let me take that from you. Looks like it weighs a ton.”

Finnerty: “I don’t want to.”

Buscemi: “Well, you need to. You need to let go.”

Little Girl: “We love you, Daddy! Don’t leave us!”

- Here, Finnerty/Tony gazes up at the trees, which always symbolize death (or at least a bad omen) in The Sopranos (The following episode’s final scene fixates on trees before Paulie beats Jason Barone).

Finnerty: “For some reason, I’m scared.”

Buscemi: “Well, there’s nothing to be scared of. You can let it go. Just come say hello.”

Finnerty: “All right.”

Little Girl: “Daddy!”

Tony clings to life as Meadow’s pleas echo throughout the Inn at the Oaks, as Tony/Finnerty can’t bring his earthly life (his briefcase) into hell, nor his identity. On some spectrum of consciousness, Tony/Finnerty understands eternal damnation awaits him in the house, hence his anxious reluctance to enter. Buscemi comments the suitcase “weighs a ton,” highlighting not just how Tony’s life has been action packed, but that he’s been incessantly weighed down by guilt, trauma, and sin. As celestial as the scene feels, it’s quite eerie knowing what awaits beyond the front door.

Additional Notes:

- In the season finale, Tony tries to reason with an unhinged, bedridden Phil: “Listen to me. Now I never told nobody this, but while I was in that coma, somethin’ happened to me. I went someplace, I think. But I know I never wanna go back there. And maybe you know what I’m talkin’ about.”

- Buscemi greets Tony/Finnerty beneath a big porch. In Season 5, Tony Soprano kills Tony Blundetto on a similar porch. In Season 4, Tony dreams of his mother on a similar porch.

- Season 4’s “Everybody Hurts” sees Tony question aloud, more than once, “am I a toxic person?” Like the coma dream, this question is one of the best exhibitions of Tony’s identity crisis.

- There is an awesome theory that poses Meadow as Tony’s guardian angel. Two examples are: her presence prevented Febby Petrulio from shooting Tony in “College.” In the finale, her arrival was too late to save Tony from his potential assassin. Here, she pleas for his life until he wakes up.