80

Cause you don’t gotta love me, but you will respect me!

Written by Frank Renzulli

Directed by Timothy Van Patten

Christopher renounces his love for Tony when Tony delays Jackie Jr.’s execution

_______________________________

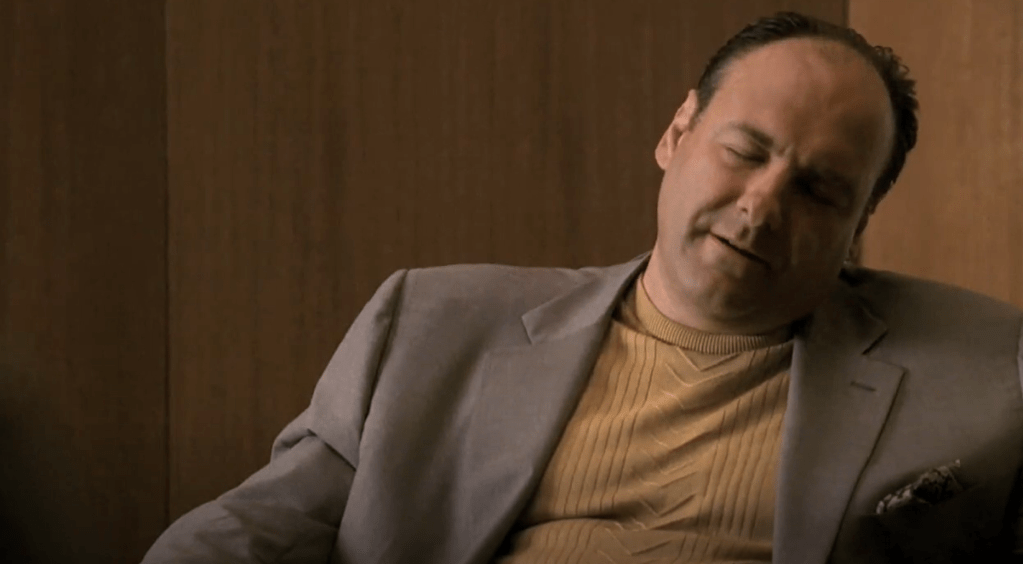

An enraged Christopher can’t comprehend Tony’s reluctance to kill Jackie Jr. after shooting at him and Furio. So, he questions Tony’s authority for the first time since the series’ fourth episode, prompting an equally heated reaction. Any animosity Christopher and Tony have had up to this point erupts in the clandestine waiting room as Dr. Fried operates on Furio’s crotch. Tony leverages Christopher’s FBI exposure to sway him away from retaliating against Jackie Jr., but Christopher sees right through the bullshit excuse, calls Tony a hypocrite, and claims he no longer loves Tony. Of all the peaks and valleys in their relationship, this feud finds itself as one of the critical valleys, and Gandolfini displays some of his best acting as he seizes Christopher by the collar and demands respect. Ironically, Christopher accuses Tony of playing favorites with Jackie Jr., neglecting how if not for favoritism, Christopher would have met his demise much, much earlier. But, Christopher’s got a point, as this is one of countless instances where Tony fails (or in this case, hesitates) to follow the Mafia Boss Code of Conduct.

79

You understand the human condition, at least

Written and Directed by Terence Winter

Tony’s fed up with therapy, and Christopher and AJ continue to make his life difficult.

_______________________________

The episode’s message, “Walk Like a Man,” backs up its title. Christopher and AJ are presented as clear parallels in the episode (just like Season 2’s “D-Girl” and Season 3’s “Fortunate Son”), and Tony has the same message for both thorns in his side: man up. Christopher struggles with sobriety, and AJ spirals once Blanca dumps him. Christopher blames his constant absence on the rampant presence of drugs and alcohol in their line of work, and Tony demands he “have some balls” and get over it. In reference to The Bing, Christopher asserts “You know, you of all people should understand how hard it is for me to be around that place.” Tony, taken aback, replies, “I should? Why?” Christopher, as earnestly as ever, then catches both the audience and Tony off guard: “Cause you’re in therapy. You understand the human condition, at least. Still doing that?” Tony changes the subject.

Later, Meadow warns her parents of AJ’s suicidal remarks, leaving Tony to seek Melfi’s counsel. In the waiting room, Tony frowns at the nude, green statue. I’m not going to try and analyze the significance of the statue itself, but I will tell you this; the very first shot of the entire series is a staring contest between Tony and the same statue. In the pilot, Tony seems intrigued, yet confused, by the statue. 80+ episodes later, he appears intolerant. In Tony’s very first therapy session, he vents about the softness of today’s generation and how everyone cries about their problems and resorts to therapy; the antithesis of Gary Cooper, “the strong, silent type.” Now, Tony resents Christopher’s weak nature, and Christopher inadvertently triggers Tony’s insecurities by sincerely inquiring about Tony’s therapy for the first time in six seasons. All the while, the camera leverages the waiting room statue to compare Tony’s first therapy session (where he demonstrates his need for and openness toward a shrink) to this therapy session (where Tony’s at his wits end with therapy). Now, he declares therapy as futile.

While the episode showcases AJ and Christopher as parallels who navigate their weaknesses, it also illustrates their similarities to Tony. Christopher highlights how, from their respective time in AA and therapy, they both understand the human condition and are in touch with their feelings. As for AJ, both he and Tony succumb to depression, and cannot simply “walk like a man” without the crutch of a shrink. For this, Tony resents Christopher, AJ, and of course himself, all for it to unleash with Melfi. All this considered, we now have the necessary context to comprehend one of Tony’s most emotional outbursts.

Per Melfi’s ultimatum in the prior episode, Tony admits he was prepared to quit therapy…until he learned AJ might be suicidal. Tony compares AJ to his peers (Jasons Gervasi and Parisi) who, unlike AJ, allegedly have their shit together. Tony then humanizes himself in rare form: “Obviously, I’m prone to depression- a certain bleak attitude about the world. But I know I can handle it. Your kids though- it’s like when they’re little, and they get sick. You’d give anything in the world to trade places with them, so they don’t have to suffer. And then to think you’re the cause of it…it’s in his blood, this miserable fuckin’ existence. My rotten fuckin’ putrid genes have infected my kid’s soul. That’s my gift to my son.” Of course, Tony attributes his son’s suffering to genetics, rather than failed parenting. Nonetheless, we see Tony humanized and vulnerable as ever; his guilt (whether misdirected or not), sympathy, and love for AJ are palpable. Tony’s tirade intensifies: “I think it fuckin’ sucks…Therapy, this. I hate this fuckin’ shit! Seriously, we’re both adults here, right? So after all is said and done, after all the complainin’ and the cryin’ and all the fuckin’ bullshit, is this all there is?”

As everything seems to fall apart for Tony, he reaches his therapeutic breaking point now that he’s passed down the same pain to his son (allegedly, solely via genetics). Yet, Tony fails to acknowledge that effective therapy demands diligent effort and full disclosure to yield results. Tony establishes his qualms and insecurities with therapy in the pilot, and glued together by the same green, nude statue, his reservations escalate into an emotional outburst fueled by AJ on the brink of suicide.

Additional Notes:

- Tony stresses greener grass for kids like Jason Parisi and Jason Gervasi, but they end up as low-level Mafia soldiers who get busted by the feds for selling ecstasy. AJ might be depressed, he might be soft, he might be a momma’s boy, and he might be a college drop out. But, AJ never fulfills Tony’s worst fear: following his footsteps into this thing of ours.

78

And maybe you know what I’m talkin’ about

Written by Terence Winter and Matthew Wiener

Directed by Alan Taylor

_______________________________

With “whatever happened there,” Little Carmine botches the truce between New Jersey and New York so severely that Phil spirals from accepting the truce to avenging Fat Dom’s suspicious disappearance (among other New Jersey transgressions) by considering whacking one of Tony’s guys. Agent Harris tips Tony regarding Phil’s imminent retaliation. Ready to execute damage control, Tony visits the acting New York boss in the hospital shortly after his heart attack. Tony’s first met by Butch and the rest of his guys, who raise their guard upon Tony’s arrival. Tony shoots by Butch’s “you should’ve called first,” and finds Ginny Sack and Patti Leotardo crying beside Phil’s bed. Once alone with Tony, a feeble Phil mutters “Finally got you to come to Brooklyn, cocksucker.” With Agent Harris’ tip at top of mind, Tony kicks it into gear.

Acutely aware Phil’s been spooked by a brush with death, Tony connects with him on a personal level. First, with their shared experiences as hospitalized cripples, but mainly as mortal sinners who’ve been consumed by the damning implications of mortality: “Now I never told nobody this, but while I was in that coma, somethin’ happened to me. I went someplace, I think. But I know I never wanna go back there. And maybe you know what I’m talkin’ about.” For the first time, Tony chillingly acknowledges the damning reality of his coma dream sequences that comprise the better part of two episodes. Upon Tony’s contemplation of life after death, Phil sheds a tear as the two come together over their likely damnation.

Aware that damnation compounds Phil’s fear of death, Tony continues: “Believe me, nobody ever laid on their deathbed wishin’ they saved more no-show jobs. Now you take your time. You get better. You get out of this fuckin’ place. But when you do, you focus on grandkids and good things. We can have it all, Phil. Plenty for everybody. Stop cryin’ now.” Phil overcompensates for being an alpha male more than anyone else in the series; he HATES weakness in any form. But, Tony finds Phil bedridden, hardly capable of speaking, and scared to the point of tears by the prospect of death…and what follows. Tony takes advantage of Phil’s vulnerable state, clenches his “fat fuckin’ hand in friendship,” (which Phil glances at in livid disgust) and tells Phil to stop crying (seven episodes after Phil completely lost his shit over Johnny Sack crying “like a woman” at his daughter’s wedding). The Sopranos, at its finest, showcases characters speaking the unspoken. Two bosses envisioning an eternity in hell as the ultimate consequence of their infinite mortal sins is as good as it gets.

Additional notes:

- It’s important to keep in mind that while Tony likely believes everything he preaches to Phil, he’s buttering him up so as to keep his guys safe, per Agent Harris’ warning. And, considering no one got whacked in the Season 6A finale, we can assume Tony’s damage control worked…for the time being.

- Tony quietly asks Ginny “How’s John?” and Ginny, unable to contain her emotions by the prospect of a wife losing her husband, avoids eye contact and raises her tissue, indicating she can’t bring herself to talk about John. It’s really good, authentic acting by the late Denise Borino-Quinn.

- When Phil declares war on the glorified crew in “Blue Comet,” Phil calls back to Tony’s visit to him in the hospital as he laments “I let him come to the hospital last Christmas and I took his fat fuckin’ hand in friendship.” In other words, Tony emasculated the fuck out of Phil.

- This is not the last time Agent Harris tips off Tony at Phil’s expense.

77

Look what his wife had to put up with

Written by Frank Renzulli

Directed by Timothy Van Patten

The wives reflect on their uniquely poisoned marriages.

_______________________________

At Vesuvio, the mob wives discuss Jackie and Meadow’s break up over lunch. Carmela, relieved over the split (unlike Rosalie), commends Meadow for handling heartbreak better than she would’ve at the same age. Gab chimes in that Meadow’s situation is “not like the grief we go through with our husbands.” Ro replies “It’s not just us. The President of the United States, for crying out loud. Look what his wife had to put up with-with the blow jobs and the stained dress.” Rosalie expresses admiration for Hillary Clinton: “All I know is she stuck by him and put up with the bullshit, and in the end, what did she do? She set up her own little thing.” While Ro may have loved her husband and still mourns him, “the grief we go through with our husbands” is behind her, all while she still reaps the rewards of a mob marriage. It’s a trade-off she seems content with.

Once Rosalie offers her words of wisdom, the camera cuts quickly to Carmela, who breaks eye contact with Rosalie and stares blankly at the table; Carm’s thinking like Ro. Five episodes later, “Amour Fou” operates as an extension of “Second Opinion,” where Carmela explores her marriage’s deep moral crisis, and ponders a life without Tony. The blunt psychiatrist, Dr. Krakower, orders her to leave Tony, and strips her of any semblance of innocence by dissecting her complicity; any blamelessness Carmela clung to evaporates. A “Fuck you Santa!” and a sleepover in the snowy woods later, “Amour Fou” opens with Carmela crying over a painting, The Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine, symbolizing St. Catherine’s “marriage” to the Baby Jesus as He’s cradled by the Virgin Mary. With her pedestal freshly shattered by Dr. Krakower, Carmela grows emotional over the purest, most innocent visual imaginable: a saint’s devotion to the sinless Christ and His Mother.

Carmela lands on a happier medium later in the hour, when Fr. Obosi proposes Carmela “learn to live on the good part” of Tony. Aligned to Rosalie’s playbook, Carmela might just be able to stick it out until Tony meets his demise. Regarding, Hillary Clinton, Carmela concedes; “well that’s true isn’t it. She’s a role model for all of us.” These women are so cheated and trapped that they have no option but to rationalize their husbands’ bullshit by applauding Hillary’s tolerance of Bill.

Additional Notes

- Tony’s exit, either to jail or from this life, would unquestionably relieve Carmela of tremendous guilt and marital torture. In Season 2’s “Commendatori,” Carmela and Rosalie hear Angie’s marital woes at Vesuvio. Angie confesses she’d rather Pussy have died than come home, and says she felt like vomiting upon his return. The episode’s conclusion mirrors Carmela’s and Angie: when Tony (gift bags in hand) announces his return from Italy, the camera cuts to Camera in the bedroom, her face flooded with mixed emotion.

- Angie also vows to divorce Pussy. Perhaps it is no coincidence she was the one to say she detests Hillary Clinton.

- Edie Falco played Hillary Clinton in American Crime Story 14 years after wrapping up as Carmela Soprano.

76

No wonder you’re having anxiety attacks

Written by Matthew Weiner and Terence Winter

Directed by Timothy Van Patten

Tony’s most revealing therapy session

_______________________________

The Sopranos follows a character incapable of and unwilling to manage the insurmountable stress he places on himself. He seeks out psychiatric counseling to curb his panic attacks, but all through his time with Dr. Jennifer Melfi, he accomplishes essentially nothing- he can’t actually discuss his true, incriminating stressors with her, or even admit them to himself. His confession about the night cousin Tony B got pinched, however, serves as a rare exception.

In a therapy scene that lasts over seven minutes, Tony recounts his panic attack with Johnny Sack on the golf course, in addition to other recent episodes. Melfi, worriedly, responds “I wish you had told me” to which Tony shoots back “I wish you’d cured it,” and claims the recent panic attacks began shortly after Melfi rejected his courtship. Normally, Tony can swiftly gloss over the truth in therapy, whether or not Melfi detects a lie. Here, Melfi’s skepticism and Tony’s guilt force Tony to inch toward full disclosure, depicting the most concrete illustration of how stress and trauma eat Tony alive:

- First, he word-vomits and blames his panic attack on cousin Tony B’s injured foot (a product of the Joey Peeps hit). Melfi, of course, doesn’t buy his weak lie.

- He then admits he worries about Tony B since he’s just out of prison, and feels guilty for Tony B’s incarceration since he too was “supposed to be there the night of the jackin’.”

- He says he missed the jacking because he was “jumped by a bunch of moolinyans,” and aggressively mutters additional racist obscenities.

- He then details how the guilt has flooded him:

- Tony: “And those 17 years, I did so good. He lost his wife, his daughter.”

- Melfi: “No wonder you’re having anxiety attacks.”

- Tony: “Yeah.”

- Tony’s body language and apprehensive delivery of “yeah” indicate Tony’s relief that Melfi acknowledged a source of his panic attacks in place of the countless other “root causes” that he’ll never be able to address with her.

- As Melfi suggests Tony come clean with Tony B, Tony blinks rapidly, jitters around his chair, and starts gasping for breath; the onset of a panic attack washes over Tony (his first ever in a therapy session). Melfi notices Tony losing it, and pries with “What is it, Anthony?” Immediately, Tony unloads:

- Tony: “Alright the night he got pinched I had a fuckin’ panic attack. From my mother, goddamn it! I didn’t even know what it was then!”

- Melfi: “Just relax. Focus on your breathing. Slowly.”

- Tony: “It’s not that, I just- I just need some Beano or something.”

- Melfi: “No, just please, focus. I’ve got my medical bag in case.”

- Tony: “Black guys, my ass. I had a fight with my mother and I had a fuckin’ panic attack!”

- Melfi: “Ok, forget that for now.”

- Tony: “Carmela was supposed to come over with some fuckin’ yarn for some bootees my mother was makin’ Meadow. She was late. What the fuck. Why go into it?”

- Melfi: “Close your eyes. Focus on your breathing.You want some water?”

- Tony: “She was carrying on. I said to her, I said, ‘Carmela loves you. You gotta understand, she’s got a three-month-old.’ But she kept fuckin’- she kept goin’ and I started screamin’ at her. So I left. I walked out the door. I went over to the car, I opened the door, boom! Cut my fuckin’ head open.”

- Melfi: “And your cousin doesn’t know this?”

- Tony: “No I lied! What am I gonna tell him? What am I gonna tell all of them? I had a fight with my mother and I- and I fainted? That’s why I missed the job. Jesus fuckin’ Christ!”

- Melfi: “That’s a lot to get off your chest.”

It is a lot to get off his chest. It’s the most sensitive reality Tony ever shares in therapy. It’s a deep, dark secret that no one’s known for 17 years. It only makes sense that finally divulging such a mental and emotional burden- compounded tenfold by its catalyst, Livia- induces a near panic attack.

Additional Notes:

- Tony recounts one of his recent panic attacks: “The cleaning girl was crying on the phone about her cousin who went off the road in a Mexican bus wreck or something. And I remember just feeling inside like I wanted to choke her cause it was always something with her.” Expressing his hyperbolic desire to harm his cleaning lady because she was sad that her cousin was either seriously injured or dead as a result of an accident is quite evil, even for Tony’s standards. It’s absolutely remarkable that Gandolfini, in one scene, can:

- Create a character that displays such a despicable disregard for others

- Complement such cruelty with a rather comedic delivery- …”cause it was always something with her”

- Showcase Tony at his most vulnerable, evoking sympathy from both the viewer and Melfi

- This breakdown leverages Tony’s “Unidentified Black Males” confession to dissect James Gandolfini’s superpowers behind the camera. I highly recommend it, as it illuminates the impressive nuances audiences normally take for granted.

- The episode’s title, “Unidentified Black Males,” refers to the Mafia’s default inclination to use black people as a scapegoat for their crimes. There are four such instances in the episode:

- Here, when Tony claims black guys jumped him before he could join Tony B on the jacking.

- When Tony asks Tony B what happened to his foot, he claims “The other night in fuckin’ Irvington two black guys jumped me outside a bar.”

- After Gene Pontecorvo beats the shit out of Little Paulie at the no-show site, he expresses concern that a civilian witness might call the cops. Vito assures him that if it comes to that, they’ll simply blame it on black people.

- Finn implies that Meadow’s ex-boyfriend was killed by Tony’s hoodlums, and Meadow relays the lie she’s been told (and consciously or subconsciously, recognizes it to be bullshit): “First of all, he was killed by drug dealers. African-Americans, if that makes you feel any better.”

- In addition to everything Tony details to Melfi, there is a huge elephant in the room that Tony must naturally refrain from discussing. Cousin Tony B, at the deployment of Johnny Sack’s rival, whacked Joey Peeps, John’s protege. Tony, better than anyone, knows Tony B may have just put relationships, dollars, and lives at jeopardy. Combine this with his 17 year long secret, and Tony might just be the most anxious man in America.

- While I have taken the time to rank the top 100 scenes in the show, I unfortunately will not be taking the time to research and document the length of each therapy session. That being said, I’d imagine the average length of a therapy scene is about 3.5-4 minutes. At 7 minutes, I’m confident this is the longest therapy session by a mile.

- This confession is a reinforcement that if he’s having anxiety attacks over this, there are about a billion other things that can provoke a Tony Soprano panic attack. This is something he actually gets off his chest, with so many other realities that will forever remain bottled up in Tony’s rotten soul.

75

And I don’t have to be confronted by that fact no more

Written by Matthew Weiner

Directed by Alan Taylor

Tony’s subconsious reveals his true feelings on Christopher’s death

_______________________________

The grim masterpiece, “Kennedy and Heidi,” explores Tony’s motive for killing Christopher, highlighted by his lingering guilty conscience (or lack thereof). Eventually, Tony sits with Melfi and laments how difficult it was “to see him die like that. Practically in my arms.” Tony quickly admits to bullshitting Melfi, and spells out relief over Christopher’s elimination, while also detailing precisely why he seized the opportunity to suffocate his protégé: “He was a tremendous drag on my emotions, on my thoughts about the future. I mean, to begin with every morning I wake up thinking, ‘is today the day that one of my best friends is gonna dime me to the FBI?’ And a weak, fuckin’ snivelin’, lyin’ drug addict? That’s the worst kind of bet. The biggest blunder of my career…is now gone. And I don’t have to be confronted by that fact no more.”

Tony’s confession elicits various reactions from Melfi. Once Tony admits “I’m fuckin’ relieved,” Melfi, very matter of fact, replies “really.” She sounds both disapproving and unsurprised. As Tony offers his rationale, her widened eyes are accompanied by a slightly dropped jaw; she seems aghast and dismayed that Tony could feel this way about the nephew she’s heard so much about over the years. As she hears Tony, she looks like she might interject, but finds herself lost for words.

Tony doubles down with “Let me tell you somethin’. I’ve murdered friends before, even relatives. My cousin Tony, my best friend, Puss. But this?” Turns out Tony was dreaming, as he awakes beside Carmela and confirms with her that he wasn’t talking in his sleep. Given Tony’s history with therapy, the ground rules Melfi set in the pilot, and the overarching purpose of Tony’s character and the guilt and trauma that deplete his soul, the viewer should’ve realized Tony was dreaming (hindsight’s 20/20).

With the series’ characters constantly repressing their moral conflicts and the dread that ensues, Chase employs this transparent dream to offer a never before seen examination of Tony’s conscience. Tony fantasizes over the stress relief that would follow with opening up about killing Tony Blundetto and Pussy. But, even in his dream state, he doesn’t allow himself to go as far as to admit that he killed someone he loved like a son. This scene, above all else, illustrates how Tony uses therapy for a band aid on a blood-gushing wound; he’ll never share the truths that cause him the most pain. Tony’s therapy remains useless so long as he refrains from discussing his deepest darkest secrets.

Additional Notes

- Right after killing Pussy in “Funhouse,” Tony uses therapy to complain about Livia as she’s caught for using Tony’s stolen airline tickets from the Davey Scatino bust out. Melfi builds on this, and pushes Tony to confront his feelings about Livia trying to kill him. But, as usual, Tony deflects and suppresses his most traumatic vulnerabilities. When she strikes out there, she pokes at Tony to dive deeper, sensing something eating at him far beyond stolen airline tickets. The Sopranos consistently shows (but doesn’t tell) how Tony grapples with something as grave as murdering his best friend. In “Kennedy and Heidi,” he finally tells us, albeit in a dream.

74

Not like we haven’t envisioned this day

Written and Directed by David Chase

Tony’s fate is confirmed

_______________________________

Starting from the very first episode, The Sopranos depicts an anxious, panic attack-prone man living in constant fear of the end. Tony’s plausibly theorized death at Holsten’s receives all the attention and analysis, but it’s this moment with his lawyer that confirms the end has come for Anthony Soprano. Through a more than apparent sequence of events, (Jason Gervasi gets nailed for selling ecstasy, and Carlo doesn’t show for a key meeting the following day) Tony deduces Carlo, a newly crowned captain, has flipped to protect his son. Like other characters in the finale, Chase captures Neil Mink, Esq.’s final appearance with a short and to the point scene.

If it wasn’t already confirmed Carlo was burying Tony to the feds, Mink reveals that somebody will be giving grand jury testimony. His hunch? “80-90% chance you’ll be indicted.” The line bears chills. It ties the bow on Tony’s saga of stress, dread, and evasion of what he always knew to be inevitable. Mink juggles the delivery of this dooming news with a helpless struggle (much like what’s to come in court) to empty his ketchup bottle en route to a healthy cheeseburger bite. This, combined with Mink’s impulse to keep staring at half-naked strippers on the security cam, demonstrates that while Tony’s worst nightmare has finally come true, it’s just another day at the office for this “white collar” lawyer. As for Tony’s abundant awareness of the inevitable, Mink’s attempt to comfort Tony instead serves as salt on the wound: “Not like we haven’t envisioned this day,” to which Tony replies “No, no it’s not.” Through Tony’s acceptance of defeat, Chase reminds the audience that he’s been spelling out the Don of New Jersey’s fate from the very beginning.

Additional Notes

- Naturally, Mink adds a sprinkle of salesy optimism with “trials are there to be won.”

73

Dead, or in the can. Big percent of the time

Tony discusses his plan to avoid the dooming fate of a mob boss.

_______________________________

The Season Four premiere, which aired September 15, 2002, uses the fallout of 9/11 to illustrate Americans’ uneasiness and uncertainty. The episode focuses on Carmela’s warning: “Everything comes to an end.” In the context of Tony Soprano and his organized crimes, the Don of New Jersey discusses the following during his visit with Melfi:

- Tony assures Melfi that, in the case of death, injury, or incarceration, Carmela will be financially set.

- Tony’s calculation: “There’s two endings for a guy like me. High-profile guy. Dead, or in the can. Big percent of the time.” But, finally he concocts a seemingly brilliant plan to minimize these odds, leaving him in quite a giddy mood

- Tony puts Junior’s situation (73, shitty house, legal bills up the ass) in perspective.

- Melfi hits Tony with a fitting “you’ve never talked this frankly” and proceeds to suggest “Anthony! Why don’t you give it up,” and Tony laughs her off and reveals his ace in the hole: bond himself inseparably to Christopher (who’s now casually shooting heroin), and use him as a shield from the feds.

When Melfi asks “Anthony, why are you telling me this?” he replies with a tender reminder that Melfi is the only person with whom he can be his true self: “I don’t know. Guess I trust you. A little.” After Tony develops the purposeful and seemingly brilliant plan to confide in only blood, we’re reminded trust is the key ingredient in ensuring things don’t come to an (early) end.

If there’s one plot point to take from this show, it’s that the prospect of death or incarceration consumes Tony every second of every day. It’s only once in a while Tony confronts this foremost stressor (re: “you’ve never talked this frankly”), and it’s especially compelling when he does so with optimism and resolve.

Additional Notes

- Lorraine Bracco’s name no longer flashes across the Twin Towers as they were removed from the opening credits

72

It’s called a handicap

Written by Jason Cahill

Directed by John Patterson

Deeper meaning spoils a tender moment between AJ and Tony

_______________________________

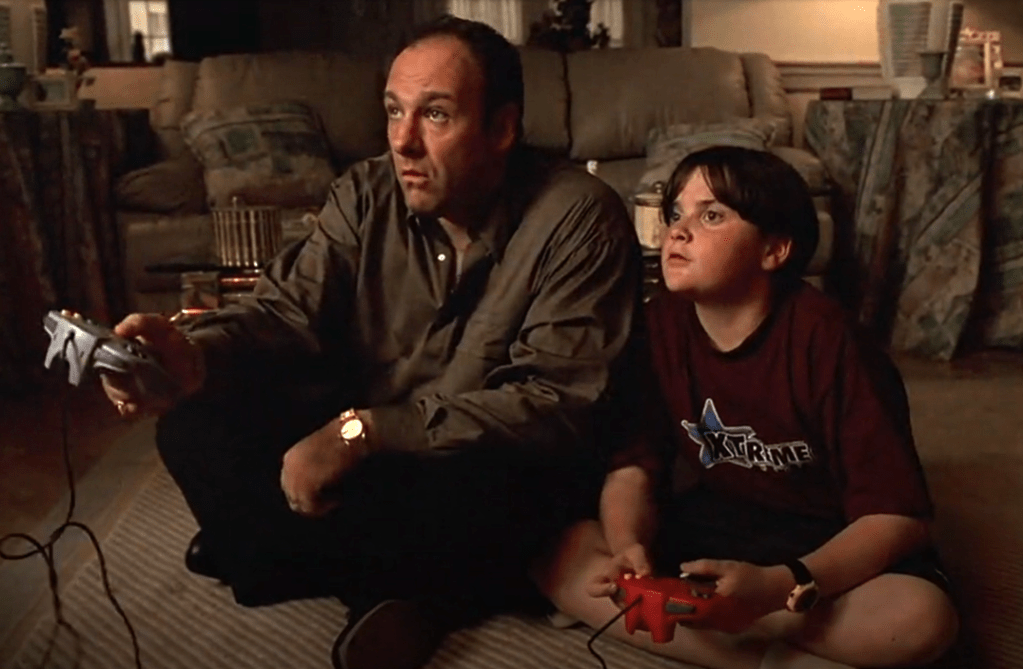

“Meadowlands” opens with Tony, beside his mistress, abruptly waking from a nightmare (the dream, located in Melfi’s office, headlines Pussy and Paulie reading the newspaper, Silvio having sex, Jackie in a hospital bed, and Livia disguised as Melfi). When Tony returns home to find AJ playing Mario Kart in the wee hours of a school night, they have quite a tender moment. Before Tony grabs a controller, AJ asks “where were you?” and Tony’s on-the-spot lie features an inconspicuous stutter, an apprehensive sniff, four guilty head rubs, and a deflective stare in the other direction (even though AJ’s eyes are glued to the screen). In an episode dedicated to AJ uncovering truths about his dad, AJ raises his eyebrows ever so slightly, suspicious of Tony’s answer.

Tony’s ensuing conversation with AJ feels like a monthly check in: “So how’re things goin’ with you? How’s school?” Perhaps if Tony chose not to come home late from his mistress’, or prioritize his loose cannon nephew or his agita-inducing uncle, Tony would have a clue about his son’s life…and maybe his son wouldn’t get into multiple fist fights with Jeremy Piocosta later in the hour. Instead, Tony uses 60 seconds of Mario Kart bonding and “I want you in bed in ten minutes” to fulfill today’s/this week’s/this month’s fatherly obligations.

Mixed in this beautifully subtle depiction of Tony’s lazy attempt at fatherhood is one of TheSopranos’ most exceptional metaphors. Tony, along with the rest of his colleagues, takes the easy way out by preying upon the vulnerable to get what he wants. While it’s just an innocent video game, and Tony playfully and lovingly horses around with his son, handicapping AJ serves as the G-Rated version of what Tony does for a living. I don’t necessarily think this metaphor was intentional, though it very well could’ve been; The Sopranos‘ writing and characters (particularly Tony) are so well constructed that all actions and words flow with consistency. These layers, filled with Tony’s faults, tarnish an affectionate moment between a father and his son who proves time and again he requires much, much more attention from his dad than the occasional, half-assed “so how are things goin’ with you?”

71

Where were you last night Anthony?

Written by Terence Winter

Directed by Steve Buscemi

A re-visited story about Johnny Boy Soprano shifts the parental blame onto him, only for Tony to keep Livia as the sole villain, aided by the consistent theme of innocent animals in danger

_______________________________

Unlike with Livia, Tony enjoys friendly dialogue with a woman once in a romantic relationship with his father. And, the new friendship is a walk in the park, until it isn’t. Tony catches on that Fran just wants to squeak money out of him, and Fran inadvertently reveals she continued smoking around Johnny Boy during his onset of emphysema. Ultimately, Fran and her stories drive Tony to one of his more painful therapy sessions. “Yeah, but I don’t fuckin’ live with my mistress. I mean, his fuckin’ slippers?” (Earlier, Fran presented Johnny Boy’s old slippers that she held onto). The slippers and Johnny Boy’s excessive time spent at Fran’s got Tony thinking. Via flashback, Tony recounts when Johnny Boy was AWOL while Livia suffered a miscarriage in the hospital. The flashback shows Johnny Boy in bed with Fran, nonchalantly responding to Tony’s news of Livia in the hospital due to bleeding arising from pregnancy. When Johnny Boy finally goes to his wife the next day, he concocts a weak excuse to an irate Livia, and pressures Tony to further the lie. With all that’s been said about Livia in therapy, this is the first time Tony expresses resentment toward his father. After the flashback, Tony protests “She could’ve fuckin’ died…from a miscarriage,” and proceeds to fight back tears. Tony pivots: “Fuck her.”

Finally, we have some character development as to why Livia grew into such a wretched senior citizen. If we now know Johnny Boy abandoned his bleeding wife and unborn baby, imagine the countless other stunts he pulled throughout his marriage. From this recollection, the audience, and Melfi, now consider the reality that Johnny Boy was the “bad” one, and his extreme unfaithfulness drove Livia to become the miserable old lady we bear witness to in Seasons 1 and 2. No child wants to admit one of their parents is awful; Tony hardly admits this even after Livia tried to kill him. So, acknowledging the same about his father is more than he can handle. Worse, if he’s the product of two malevolent parents, what does that make him? Melfi, abundantly aware of Livia’s traumatic mothering, shifts the blame away from Livia, for once: “Was there any blame on his part? This man you emulate? The lies? The betrayals with other women? Listen to me, this is very important. Your mother had her faults, but after all this time what should we do with the old woman? Have an auto-da-fe? Burn her at the stake? You need to forgive her and move on.” Tony does the opposite: “She made my father give my dog away…probably didn’t wanna deal with her bullshit anymore. He gave my dog away to his girlfriend’s kid. Big deal. It was up to her, she woulda had it killed.”

Throughout this therapy session, Tony finds himself on the brink of a diatribe against his father, but he holds back. With all his bitterness toward his mother, now complicated by this image of her helpless and alone in the aftermath of a miscarriage, Tony must scratch and claw to perpetuate the fallacy that “Johnny was a saint.” To do so, he applies the most effective method to denigrate Livia: he hypothesizes she’d be willing to kill Tony’s pet dog for convenience sake. Regularly throughout the series, Tony grows emotional over the idea of animals being harmed. He cries when the ducks leave the pool, sobs to Melfi when Ralph burns Pie-O-My, and threatens to suffocate Christopher when he learns he accidentally killed Cosette. Now, he leverages the prospect of Livia killing his dog to re-fuel his hatred for his mother and distract from his newfound resentment toward his father. The scene impressively combines the effect of animals on Tony with the human instinct to deny the hard truth by manufacturing your own truth.

Additional Notes:

- When Melfi finally reads the study that forces her to realize that, for Tony, therapy is just “one more criminal operation,” the text highlights how “the criminal’s sentimentality reveals itself in compassion for babies and pets.”

- Fran discusses her fling with JFK during his presidency. In this episode’s final scene, Tony completely embellishes this fling to Sil, Tony B, and Artie. He claims that Fran and JFK dated for three years with regular trips to the White House, leaving Jackie Kennedy questioning the stability of her marriage. Sil and Tony B know Tony’s overcompensating, and the episode’s final shot zooms in on Tony blowing cigar smoke (hence, blowing smoke up his friends’ asses). Here, we have another example of Tony working overtime to put his dad on a pedestal.

- Could you imagine being sixteen years old and pressured by your father to lie to your mother under these circumstances? Conversely, Livia certainly resented Tony for this. Perhaps everything Livia gave Tony a hard time about as an adult (e.g., placing her in Green Grove) was rooted in topics she refused to confront, like teenage Tony lying to her.

- Melfi usually pushes Tony to confront his feelings about Livia, and he seldom does. This is the only instance she pushes him to forgive Livia. It’s apparent Melfi was influenced by this new side of the story, as she (for once) sympathizes with Livia.